|

A fundamental human need is to help others. Many individuals do not recognize the need, and others do not seek to satisfy the need. Although charitable organizations, including churches, present numerous opportunities to give money or to physically work at specific events, they fail to present opportunities in the marketplace where individuals can physically contribute spontaneously and for limited duration. We present one example suitable for a street fair: repackaging bulk foods into smaller amounts distributable to individuals and families by charitable hungry-relief agencies. The author solicits theoretical and real-world examples suitable for shopping malls, night scenes, and even resorts.

|

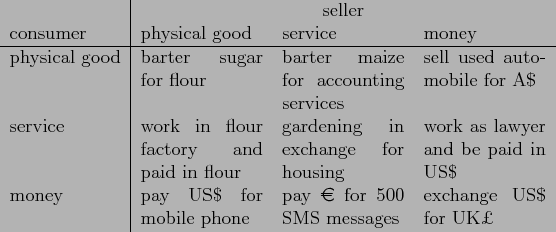

Charitable organizations invert the typical marketplace model where

consumers seek items to satisfy their needs or wants. In the typical

model, a consumer obtains physical goods, services, or money made

available by a seller in exchange for money or sometimes physical

goods or services. (See Table ![]() .)

For example, a consumer may pay money to obtain the physical good of a

loaf of bread. All combinations of exchange exist. For example, a

consumer may pay money, e.g., U.S. dollars, to obtain money, e.g.,

U.K. pounds, or a consumer may pay a service in exchange for money,

e.g., employment's leading to a paycheck. Admittedly, money, by the

reason for its existence, is most frequently used.

.)

For example, a consumer may pay money to obtain the physical good of a

loaf of bread. All combinations of exchange exist. For example, a

consumer may pay money, e.g., U.S. dollars, to obtain money, e.g.,

U.K. pounds, or a consumer may pay a service in exchange for money,

e.g., employment's leading to a paycheck. Admittedly, money, by the

reason for its existence, is most frequently used.

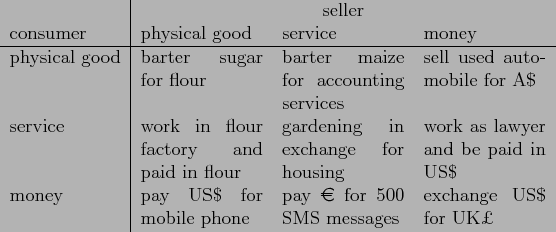

Charitable organizations sell consumers the opportunity to satisfy

their needs or wants to give, not receive. Existing organizations

permit consumers to give physical goods, services, and money. (See

Table ![]() .) Typically, these are planned

transactions usually in physical locations separate from

non-charitable organizations. For example, a volunteer may donate a

day of labor building a house at a Habitat for Humanity site. The

volunteer prepares, wears the proper clothes, registers in advance,

and travels to a specific site dedicated to Habitat. In another

example, a donor may deliver gently used clothing to a battered

women's shelter. This is typically planned, but perhaps not

scheduled, because the donor must gather the clothing and deliver it

to a specific site.

.) Typically, these are planned

transactions usually in physical locations separate from

non-charitable organizations. For example, a volunteer may donate a

day of labor building a house at a Habitat for Humanity site. The

volunteer prepares, wears the proper clothes, registers in advance,

and travels to a specific site dedicated to Habitat. In another

example, a donor may deliver gently used clothing to a battered

women's shelter. This is typically planned, but perhaps not

scheduled, because the donor must gather the clothing and deliver it

to a specific site.

Donating money is the charitable activity that can be most spontaneous and occur in the ordinary marketplace. In the States, charities will send unsolicited mail in December hoping for spontaneous, end-of-the-tax-year donations. The Salvation Army sends donation collectors into the marketplace during the Christmas shopping season hoping for spontaneous donations. The Lance Armstrong Foundation has done a superior job of selling donation opportunities through its plastic Livestrong wristbands, which reward the donor and also advertise the donation opportunity to others.

Spontaneous charitable donation of physical goods in the marketplace on a continuing, organized basis seems difficult because few Westerners carry physical goods to donate. The closest example the author knows is canned food collection bins in food stores. Of course, beggars in the marketplace have solicited spontaneous donations of physical goods for millennia.

Providing opportunities for spontaneous contributions of services by people in the marketplace is an unfilled opportunity. Consider a street fair, which typically has tens of booths selling food and items to visitors for money. People attend and spend money to fill their needs and wants. A charity could easily sponsor a booth to collect spontaneous donations, but it could also provide the opportunity for street fair visitors to spontaneously donate services and satisfy their need to help others. A food bank could provide the opportunity for visitors to repackage 50kg bags of rice and beans, donated elsewhere, into 1kg bags suitable for distribution. Visitors could participate for thirty seconds or hours. This example illustrates several principles and best practices for spontaneous contributions of services in the marketplace.

Best practices for spontaneous contributions of service in the marketplace including the following.

This document was generated using the LaTeX2HTML translator Version 2008 (1.71)

Copyright © 1993, 1994, 1995, 1996,

Nikos Drakos,

Computer Based Learning Unit, University of Leeds.

Copyright © 1997, 1998, 1999,

Ross Moore,

Mathematics Department, Macquarie University, Sydney.

The command line arguments were:

latex2html -split 2 -no_navigation -link 0 -nofootnode selling-charity-20110813.ltx

The translation was initiated by Jeffrey Oldham on 2011-08-13