Giving and taxes: advanced strategies

This article covers a few unrelated strategies, for those who already know they plan to give over the next 2-10 years. The article assumes you've read Giving and taxes, and are moderately comfortable with financial stuff. If that's not the case, please reach out and I'd be happy to walk through the details and/or help set up the relevant accounts over a phone call or zoom.

I'd also love to know if you do implement or have already implemented any of these, as well as any other techniques you may have seen!

Structure a portfolio for giving

In Giving and taxes, we saw the tax benefits of donating highly appreciated stocks. These are stocks whose cost bases are much lower than their current market price. However, what if you don't have highly appreciated stocks to give?

If you already know you are going to give away some fraction of your savings over the next 5-10 years, you can structure your investments to (greatly) decrease the cost bases of the stocks you end up donating. Moreover, the tweak needed is relatively straightforward if you already put your money into index funds.

Capital gains concentration

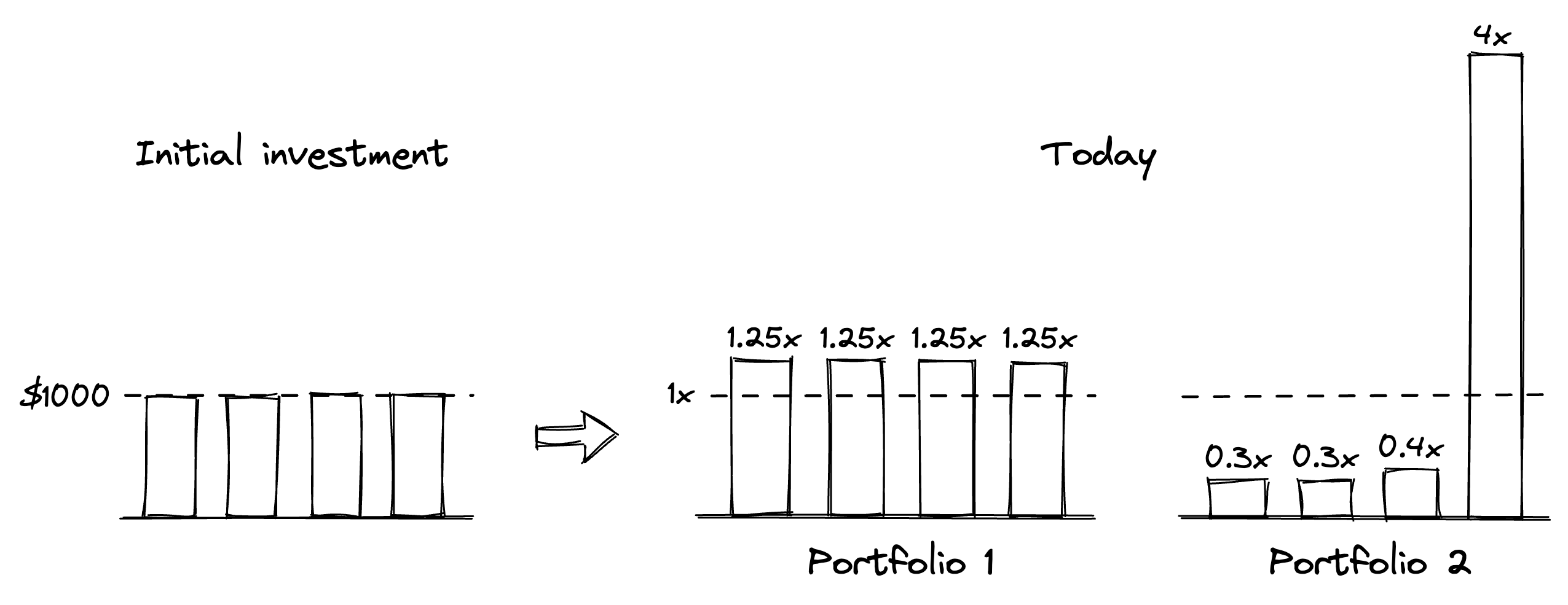

Let's take two hypothetical portfolios, a few years out from the initial investment. Both started with $4000, spread equally over 4 investments. Both portfolios are worth $5000 today, pre-tax. Each bar is a stock or index fund in the portfolio:

Both portfolios have appreciated the same amount, and have the same total cost basis. But Portfolio 2 is substantially better from the perspective of a donor!

Let's say you donate $100 from the portfolio. In Portfolio 1, the cost basis of any $100 of the portfolio is $80 [= $100 / 1.25]. In other words, any $100 of the stock today started out as $80 of the initial investment.

In Portfolio 2, the cost basis of $100 from the 4th bar is $25 [= $100 / 4]. Any $100 from the 4th bar started out as only $25 of the initial investment.

Let's use the tax bracket assumptions from Giving and taxes. The only one we'll need is the total capital gains tax, which is 30% [= 15% federal + 11% state + 4% NIIT].

In Portfolio 1, the $100 donation is essentially resulting in a "free" $6 [= 30% * ($100 - $80)] from long term capital gains forgiveness. In Portfolio 2, the $100 donation results in a free $22.50 [= 30% * ($100 - $25)] for the same reason [1].

That's an extra $16.50 [= $22.50 - $6] difference on just a $100 donation!

The exact numbers depend on your capital gains tax bracket and how low you can drive down the cost bases in Portfolio 2. But in many high tax bracket situations I think it's pretty easy to beat index funds if you already expect to be donating stuff down the line.

Direct indexing

The simplest way I know of to passively implement the above is to switch from buying index funds to direct indexing (with tax loss harvesting). The link explains the difference between index funds and direct indexing; it's worth reading that first.

There are two reasons direct indexing works so well for donations in particular, relative to using index funds:

- Even though the stock market as a whole tends to grow, most public companies lose value over any several-year period, and most of the gains are concentrated in a relatively small number of companies. In other words, the set of publicly traded companies already kind of looks like Portfolio 2.

- Tax loss harvesting works better in a direct index (relative to tax loss harvesting on a set of index funds), since the individual components of an index are way more volatile than the index itself. This is a primary premise behind direct indexing in general, whether or not you donate. But it pairs particularly well with donation, since you get to permanently keep the harvested losses.

The idea here is to put the money into a direct index, wait a few years, and then each year donate from whatever is most appreciated at that moment in time [2]. The direct indexing service will take care of reshuffling your other positions to get it back to looking like your original portfolio.

Implementation: A number of major brokerages offer direct indexing (often marketed as "personalized indexing"). The main features to look for are

- Whether you can see and remove the "winners" from the index, ideally, at the lot level.

- Whether the index includes US small cap and emerging market stocks.

- Whether you need to sign up for a financial advisor in order to access direct indexing.

- Fees. As of early 2023, most of them hover around 0.4%/year.

Schwab seems to have a reasonable one, though I don't have personal experience with it, or a strong reason to believe it is better than others [3]. You need to talk to a Schwab financial advisor to sign up, but it seems like you don't need to be in a paid relationship with an advisor to use it.

If you already have a relationship with a financial advisor, they almost certainly have access to a high quality direct index. Natixis and OSAM Canvas are two example providers, but there are many others. Prices should be lower, like 0.2-0.3% a year.

In all cases, direct index fees will be higher than just buying the underlying index funds (the comparable Vanguard index funds are ~0.03-0.1%/yr). Direct index services argue that the fees pay for themselves via tax loss harvesting, even if you never donate anything. This is plausible if you have ongoing capital gains to offset, or expect to never sell down your entire portfolio.

Assuming neither of those is true for you, I'd say the fees and complexity start to be worth it if you expect your annual donations to average at least 1-2% of the amount you put into the direct index. The threshold can vary though depending on your capital gains bracket, portfolio size, and various modeling assumptions, so feel free to reach out if you want to run through the calculations for your particular situation.

Bonus: This can be paired with the DAF strategy for highly appreciated shares to extract even more capital losses. Each year in December, take anything worth more than 2x its cost basis (that you've held for at least a year), and put it into the DAF. In April, take the extra refund resulting from the itemized deduction, and put the refund back into the direct index, to extract losses from the refund as well.

Going (even) further: Tharu and I spent some time in 2022 exploring ways one could concentrate capital gains even further, if one were willing to put in an arbitrary amount of work. We don't currently have anything to recommend, but if you're handy with this stuff we'd love to run some of these ideas by you.

I suspect this won't apply to most readers, so the rest of this section is collapsed by default.

Other implementation strategies

At a high level, all of these strategies are trying to find a set of highly volatile securities that are uncorrelated enough to be combined into a sufficiently stable component of your portfolio. In the case of a direct index, the securities are the set of publicly traded companies.

Some alternate ideas are listed below. Take everything here with a grain of salt; these are notes from an initial investigation, and we didn't double check any of it before putting it here.

- Tilt the direct index above towards smaller cap stocks

- It seems very likely there is an incremental improvement to be made to the standard (i.e. modern portfolio theory) index allocation, if you can model the positive impact of the tilt on the cost basis of the things you donate, and compare it to the negative impact on expected returns and volatility of the portfolio as a whole.

- A related strategy could be to aggressively tilt the direct index towards small cap stocks, and then hedge the position by shorting (or by buying put options on) a small cap index fund.

- Maybe the tilt should instead be towards growth stocks? Momentum stocks?

- Use an options strategy, e.g. buy far out of the money call options and then hedge the position

- Ideally you'd have a set of positions where you'd expect to lose money on most, and have a 10x gain on a few.

- A big consideration here is that only long term capital gains are forgiven in a donation. So the options need to be LEAPs; the underlying security probably needs to be a stock (index options are taxed differently), and money made on a put may not count. This article has some good information.

- Once you're looking a year out, the market is pretty thin, and bid-ask spreads are high, even on generally well-traded names.

- Options premiums are deductible as a capital loss (an important prerequisite for this strategy to work at all).

- Vanguard Charitable can directly accept unexpired options. They will be sold shortly after transfer.

- Buy a basket of pre-IPO stocks, e.g. via an investment advisor, fund, or Equity Zen

- The premise here is that the year surrounding an IPO is a particularly high volatility period for the company.

- If doing this via a fund, need to make sure the fund intends to give the post-IPO distributions in stock rather than cash.

- Open question: Ignoring fees, how does randomly selecting pre-IPO companies on EquityZen do relative to market returns? Intuitively I would worry about adverse selection, but the people I know who are more familiar with EquityZen don't seem as worried.

- EquityZen fees seem to be 5-10%. Not sure how that compares to an advisor or fund.

- Buy crypto alt coins

- Alt coins are I assume highly volatile, though I don't know if they are also overly correlated.

- Open question: Does a basket of random alt coins have a reasonable expected return? Or should one expect it to under-perform the market?

- Open question: Any reason to prefer this over a basket of small cap stocks? Or penny stocks?

- daffy.org (DAF) accepts ~120 alt coins. That's a lot but also not that many compared to the number of public stocks.

- A donation would need a potentially expensive appraisal. If doing this strategy, we would need to check with https://cryptoappraisers.com to see how many coins can be appraised.

Sometimes a DAF can help

A Donor Advised Fund (DAF) allows you to pre-allocate money for future donation. Daffy is a reasonable provider, with fees capped at $20/month [4]. You can put up to 30% of your pre-tax income for stock donations (or roughly 50% for donations overall) into the DAF in any given year and get the full benefits listed in Giving and taxes. The general idea is to put several years worth of donations into the DAF up front, and then pay charities out of the DAF over time.

A DAF doesn't always help, but when it does, it can save thousands of dollars a year. I'll cover three such situations below.

Your income tax bracket is about to drop

The itemized deduction benefit is proportional to your income tax bracket. Here are some situations where you could reasonably expect your tax bracket to be higher now than it will be for the next few years:

- Company IPO

- Retirement

- About to move from California or New York to anywhere else

In these situations, you put the money into the DAF while you are in a high tax bracket, and get an itemized deduction based off of that high bracket. In subsequent years, you donate from the DAF, on your originally intended schedule.

Note that changes to your capital gains bracket don't matter here; only changes to your (federal + state) income tax bracket.

Your non-charity deductions don't hit the standard deduction threshold

If your non-charity itemized deductions don't normally hit the standard deduction threshold (which is most people that don't have a mortgage, regardless of your state), you can often save quite a bit by bunching your donations via a DAF. The idea is: each even numbered year, donate directly to the charity, and put an equivalent amount into a DAF. Each odd numbered year, donate to the charity from the DAF.

As an example, let's take a married couple that donates $30k/year. They have $10k in SALT deductions, and their federal standard deduction is $27k.

Without a DAF, they directly donate $30k each year. They have

$40k [= $30k direct donation + $10k SALT] of itemized deductions the first

year,

$40k [= $30k direct donation + $10k SALT] of itemized deductions the

second year,

for a total of $80k of itemized deductions at the federal level over the two years.

With the every other year DAF strategy, they have

$70k

[= $30k direct donation + $10k SALT + $30k DAF donation] of itemized deductions

the first year,

$27k [= standard deduction] of itemized deductions the

second year,

For a total of $97k of itemized deductions at the federal level over the two years.

That's an extra $17k [= 97k - 80k] of itemized deductions every other year, which is about $2k [= 17k * (15% + 4%) capital gains tax / 2 years] of extra cash in their pocket each year!

A similar calculation applies at the state level, in most states [5].

You can also do this every 3rd year, instead of every other year. You'd put 2 years of donations into the DAF at once, and then donate from the DAF the following 2 years. That would increase the savings federally from $2k/year to $3k/year.

You have highly appreciated shares slated for future donation

If you have cash slated for future donation, putting it into a direct index usually makes more sense than putting it into a DAF, assuming the two sections above don't apply.

However, if you have appreciated shares (let's say, shares more than 2x their cost basis), it's not easy to extract further capital losses from a direct index. In that case it often makes sense to put them into a DAF.

Let's take as an example $100 of GOOG, with a cost basis of $30, that you want to donate in 10 years. Let's assume the market [6] doubles in that time, as does GOOG.

Let's also use the tax bracket assumptions from Giving and taxes, and say that your total income tax is 46% (federal + state).

Without a DAF, you would donate $200 in ten years, and get $92 [= $200 * 46%] back as an itemized deduction at that time.

With a DAF, you would put $100 into the DAF right now, and get $46 [= $100 * 46%] back now. After ten years, the $100 in the DAF would be worth $200, and you'd donate that. Meanwhile, the $46 would turn into $92 [= 2 * $46].

So far everything looks pretty similar! The difference is that in the DAF scenario, the $46 could itself sit in a direct index for those 10 years, allowing you to further extract capital losses.

Note that this only makes sense if you would be interested in donating the $92 at the end of ten years (in addition to donating the $200). If you wouldn't, keeping it out of the DAF is probably better, since in that case at the end of 10 years your $92 will have a cost basis of $92, rather than a cost basis of $46.

Get a registered domestic partnership (CA, NV, and WA)

If you are in California [7], and planning to get married, consider getting a registered domestic partnership (RDP) instead. The rights and responsibilities are essentially the same as marriage at the state level (it's hard to get divorced, businesses can't discriminate based on the difference between RDP and marriage, and so on). You can transition an RDP to marriage [8] if you leave to a state that doesn't recognize California RDP, or need some federal right, like adopting internationally [9].

I have an extended doc on the tax benefits and other considerations that I am happy to send, but at a high level I expect many high earning couples would pay $4-20k/yr less in taxes (as compared to marriage), depending on their exact situation. This applies even if you don't donate at all.

The only situation I know of where RDP has a tax disadvantage relative to marriage is if one person would come into the union with a large number of AMT credits or capital losses. At the federal level, those AMT credits will be split among the two partners in marriage, but not with a California RDP [10].

The place this intersects this doc is: as a married couple, both people have to take the standard deduction or both people have to itemize. You can't mix and match, even as married filing separately. As an RDP, one person can take the standard deduction, while the other person itemizes. This means you get the full benefit of itemizing + a "free" standard deduction relative to filing as married. Assuming you donate enough to itemize, and don't have other itemized deductions, this benefit is worth $4-6k/year alone.

Taking full advantage of this does require donating from separate property, rather than community property. If you donate less than $34k/yr this is very straightforward, and requires no action other than reporting it correctly on your taxes. Donating more than $34k/yr does require advance planning, though on the plus side, in CA it can result in some additional savings on your state taxes.

Closing remarks

The above is likely an overwhelming amount of information, for almost anybody. Alternatively, you might be wondering about various calculations or model assumptions that were glossed over.

If you already know you're going to be donating significant amounts in the future, please don't let either of the above stop you from taking advantage of these. I'm happy to talk to you (or directly with a financial advisor) to figure out if there are any simple changes to your financial setup that would make sense.

In general, the goal of all these strategies is to

- Maintain exactly the same financial exposure you currently have, but

- decrease the amount you pay in taxes,

- using the fact that you already plan to donate $X/year over the next 2-10 years.

Philosophically, I think making donations cheaper has a huge effect on how much people donate. If you don't think about taxes, it in some ways can feel like a direct tradeoff: would I rather have one dollar, or would I rather that dollar go to someone else? Between Giving and taxes and the strategies here, the question becomes closer to: would I rather have one dollar, or would I rather four dollars go to someone else? There are a lot of holes in that argument as stated, but I'll expound on the thought in a different post.

Footnotes

[1] The itemized deduction benefit is the same in both cases, so we ignore it here.

[2] And that you've held for at least a year. Most on-line brokerage accounts will show separate columns for unrealized long term gains and unrealized short term gains; you want long term.

[3] Tharu and I have a provider that we like, but they recently started requiring new clients to also pay for a financial advisor :/.

[4] Most DAF providers charge an order of magnitude more, so if you go with another provider make sure to do the math out on their pricing.

[5] The CA reduction in itemized donations (see section with that name) can actually make the impact even more extreme in CA. Bunching two $30k deductions can result in an extra $1-2k of savings at the state level, vs the roughly $500 [= $10k standard deduction * 11% / 2 years] you'd expect without that.

[6] "The market" meaning Daffy's default portfolio, which will be some blend of index funds. Many DAFs (including Daffy) won't allow you to continue to hold the donated shares as GOOG; any asset you put into a DAF is converted into one of a handful of DAF-supported portfolios as soon as it arrives.

[7] Nevada and Washington state also have the relevant structure, which is domestic partnership with community property benefits. I expect they aren't too different from CA, but I haven't looked in detail.

[8] Meaning, you can just file the normal marriage paperwork, and be both RDP and married. You can hold both statuses simultaneously as long as they are with the same person.

[9] One common case where RDP may not make sense is if one or both partners are not US citizens.

[10] Any AMT credits or capital losses acquired in the year of the RDP or later are totally fine; they are split the same way as marriage.

Date: April 2023

Author: Rishi Gupta