The Markov and Chebyshev Inequalities

We intuitively feel it is rare for an observation to deviate greatly from the expected value. Markov’s inequality and Chebyshev’s inequality place this intuition on firm mathematical ground.

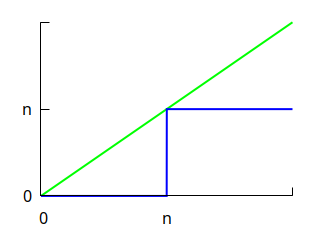

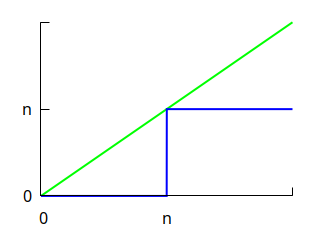

I use the following graph to remember them.

Here, \(n\) is some positive number. The blue line (the function that takes the value \(0\) for all inputs below \(n\), and \(n\) otherwise) always lies under the green line (the identity function).

Markov’s Inequality

Suppose \(n\) is a positive integer. Since the blue line lies under the green line:

\[0 + … + 0 + n + n + … \le 0 + 1 + 2 + … \]

Suppose the random variable \(X\) takes nonnegative integer values. Let \(p(i)\) be the probability of \(i\) occuring, and multiply the \(i\)th term by \(p(i)\):

\[ 0(p(0) + … + p(n-1)) + n(p(n) + p(n+1) + … ) \le 0 p(0) + 1 p(1) + 2 p(2) + … \]

In other words, we have Markov’s inequality:

\[ n \Pr[X \ge n] \le E[X] \]

The graph captures this inequality, and also makes it clear why equality is attained only when \(p(i) = 0\) for all \(i \ne 0, n\) (the only two points where the two functions agree).

The argument generalizes to any random variable that takes nonnegative values.

Chebyshev’s Inequality

We start from Markov’s inequality:

\[ \Pr[X \ge n] \le E[X] / n \]

Then we complain about the \(n\) in the denominator. The bound is so weak. Can’t we do better than a denominator that increases only linearly? Why not at least quadratically? Why not \(n^2\)?

No problem! We simply square everything:

\[ \Pr[X^2 \ge n^2] \le E[X^2] / n^2 \]

[Actually, we cannot square quantities arbitrarily. More precisely, we have replaced \(n\) by \(n^2\), and are now considering the random variable \(X^2\) instead of \(X\).]

But nobody likes \(E[X^2]\); everybody prefers the related \(E[(X - E[X])^2]\), aka the variance. In general, we prefer central moments to raw moments because they describe our data independently of translation.

Thus we replace \(X\) by \(X - E[X]\) to get Chebyshev’s Inequality:

\[ \Pr[(X - E[X])^2 \ge n^2] = \Pr[|X-E[X]|\ge n] \le E[(X - E[X])^2] / n^2 \]

We let \(\mu = E[X]\) and \(\sigma = \sqrt{E[(X-E[X])^2]}\), and substitute \(n\) with \(\sigma n\) so it looks better:

\[ \Pr[|X-\mu|\ge \sigma n] \le 1 / n^2 \]

We can remove the restriction that \(X\) is nonnegative: the random variables \(X^2\) and \(|X - \mu|\) are nonnegative even if \(X\) is not.

Weak Law of Large Numbers

Let \(X_1,…,X_N\) be independent random variables with the same mean \(\mu\) and same variance \(\sigma^2\). Define a new random variable:

\[ X = \frac{X_1 + … + X_N}{N} \]

Then:

\[ \Pr[|X - \mu| \ge \alpha] \le \frac {\sigma^2 }{ \alpha^2 N} \]

Proof outline: Show \(E(X) = \mu\) and \(\operatorname{var}(X) = \sigma^2 / N\) then apply Chebyshev’s inequality.

Higher Moments

A similar argument works for any power \(m\) higher than 2. None of them are named after anyone, as far as I know. For any random variable \(X\) and positive \(n\), we have:

\[ \Pr[|X| \ge n] \le E[|X|^m] / n^m \]

and:

\[ \Pr[|X-\mu| \ge n] \le E[|X-\mu|^m] / n^m \]

Viewing the moments \(E[X^n]\) as coefficients of a power series yields the moment generating function, which leads to a proof of the central limit theorem. This theorem features the normal error curve. Sometimes, practitioners hallucinate its presence, with interesting consequences.

Stahl, The Evolution of the Normal Distribution, describes exactly when to expect a normal distribution while taking us through its history. Did you know the greatest minds struggled with this now-commonplace curve? Gauss’s first derivation uses circular reasoning, which may have been why he twice revisited the problem. And although Laplace implicitly justifies the normal curve in his proof of the central limit theorem, he had proposed different odd-looking error curves on two separate occasions.

An Exponential Improvement

Under some conditions, we can get a denominator that increases exponentially. In other words, large values of \(\Pr[|X-\mu|]\) are almost impossible: the Chernoff bound.

For randomized algorithms, exponential bounds are more useful than the law of large numbers or the central limit theorem. For instance, what are the chances a quicksort goes far slower than expected? It’s not enough to know that some sequence of distributions eventually converges to something nice; we want practical algorithms with overwhelming odds of success.